Significancy of Agribusiness

Concentration in Coffee’s Food System

If you are a coffee-lover, you may be interested in

what processes a cup of coffee has come through to your hands. Almost all

coffee beans are produced by family-managed farmers in developing countries, such as Brazil, Vietnam, and

Colombia, and pass very complicated routs between them and you: local coffee

bean dealers in rural villages, exporting firms in producing countries, trading

companies in your country, roasting and packing agencies, and your favorite

cafes if you have some out. A chain of relevant subjects, such as those above,

and correlation between them in food production and distribution are called the

food system. As shown in the case of coffee’s food system, some food systems

consist of worldwide networks connecting farmers in developing countries and

consumers through food firms. In such international networks, as consumers are

distanced from farmers in food systems, roles of agribusiness firms between them

are significant because the firms need to reflect consumers’ demand for

products on farmers’ production plans over boundaries. This system which

benefits consumers, in turn, sometimes damages producers’ economies in

developing countries, which results from a difference of bargaining power

between farmers and firms. For example, in coffee’s food system, almost all

intermediate businesses are concentrated on a few large-scale multinational

corporations; therefore, some small-scale coffee farmers suffer from unfair

contract conditions in trading with them (Tsujimura p.96). In this essay, it is

investigated how such concentration of agribusiness has been built on coffee’s

food systems, what effects the intensive agribusiness structure causes on the

food systems in developing countries, particularly on farmers living there, and

what is prospects for the globalized food systems.

Business concentration in agricultural industries

frequently appears in food systems of developing countries for three reasons: a

tropical climate in low latitude areas, a remaining relation with suzerain

countries in the colonial period, and an economic aid of the IMF and the World

Bank since 1968. The first reason is a geographic factor in developing

countries; these countries’ climate are perfect for tropical farm products such

as coffee beans. Major breeds of coffee beans have their biological origin in

tropical areas of African countries like Ethiopia and Congo, so cultivation of

them basically requires a high-temperature and high-humidity climate.

Accordingly, agribusiness of coffee production is only around low latitude

areas in which most developing countries are located. The second reason is the

colonial history of some developing nations. A primary purpose of establishing

colonies for European countries was production of tropical foods just like

coffee beans and tea leaves, and international trades of these products was

traditionally monopolized by a small number of enterprises; the same custom is

left over current food systems of some tropical products (McMichael p.151).

Finally, economic supports of the IMF and the World Bank on developing nations

in the late 20th century has unexpectedly intensified agribusiness

concentration in those countries. A general goal of the support programs was

improvement of poor populations’ income in developing countries, most of which

engaged in the primary industry; thus, the organizations proceeded technical

and financial supports in agricultural industries by means of introduction of

high productivity breeds and transition to more profitable cash crops,

including coffee beans as a target crop. As a result of this policy, most

farmers under the supports switched their farming style from self-sufficient

one to commercial one, which also created extended business chances for

agribusiness firms (Araghi p.182, Toyoda p.78). These elements in a business

concentration process has together helped international trade corporations to

grow into a huge scale which covers a whole food system from its top to the end.

Such an intensive agribusiness structure in

developing countries works against farmers in price setting process. In fact,

they lost their bargaining power in

negotiations for price setting. This is because individual farmers with

relatively slight amounts of supplies has no influence against large-scale

corporate groups which dominate almost all stages of a food system. This

phenomena is illustrated by a case study of coffee’s food system in a rural

farming area of Tanzania, namely Mt Kilimanjaro and its surrounding region, by

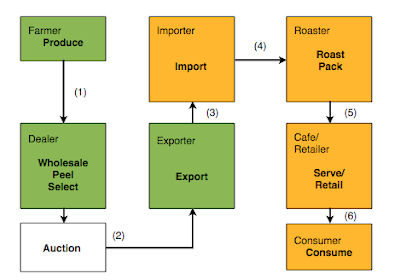

Tsujimura. A whole food system of Kilimanjaro coffee is shown in Fig.1; within

Tanzania, a regional food system consists of three subjects: farmers, dealers,

and exporters. In this case, all local dealers and exporters are subsidiary

companies of multinational trade corporations which put their headquarters on

European countries, as shown in Fig.2; consequently, the stage (2) in Fig.1 is

a pure inside trade although the trade officially forms a public auction style.

As an example for the stage (1), in Lukani

village, a main survey field of Tsujimura, local coffee bean dealers are only

three groups while 355 houses sells coffee beans individually. This transaction

is completely run by the dealers; the price is decided by subtracting whole

distribution costs from a selling price at the stage (3).

Figure 1: Global Food System of Kilimanjaro Coffee

Note: Green Box=Tanzania, Yellow Box=Japan (ex.)

Source: Tsujimura p.73

Figure 2: Dealing and Exporting Share of Kilimanjaro

Coffee

Subsidiary

|

Dolmen

|

Taylor

Winch

|

ACC

|

Olam

|

Parent

|

ED&F

Man

|

Volcafe

|

Schurter

|

KC

Group

|

Headquarter

|

U.K.

|

Switzerland

|

U.K.

|

Singapore

|

Dealing Share

|

20.7%

|

14.8%

|

14.6%

|

10.8%

|

Exporting Share

|

33.8%

|

15.9%

|

8.4%

|

8.3%

|

Note: ACC=African Coffee Company. Volcafe was merged

into ED&F Man in 2004.

Source: Tsujimura p.93

In addition, the price at the stage (3) itself is

unfair for Tanzania’s local farmers. Tsujimura (p.81) continues an

international trade price for coffee beans is based on a futures price at the

New York Board of Trade (NYBOT) where the price for coffee beans is decided

mainly by an expected yield in Brazil and a speculation trend, regardless of

any factors in other producing countries. Moreover, this international price

fluctuates as shown in Fig.3 because of a synergy between speculation and

uncertainty of Brazil’s yield like weather; for instance, if unreasonable

weather in Brazil is forecasted before a cropping season, investors will flood

into buying, anticipating a rise in a coffee price at the NYBOT, which expands

a fluctuation range. Overall, Tanzania’s farmers have to respond to an

unreasonable and changeable price which they are not responsible for.

Source: International Coffee Organization

Also, it is pointed out that the food system of

Kilimanjaro coffee contributes unjustly small amounts to Tanzania’s national

profit in international trading. According to a statistic of 1998’s

international trade of Kilimanjaro coffee with Japan, the biggest importer of

the coffee, an annual disposable income in Tanzania was only 35.87 million US

dollars whereas Japan got more than 1 billion US dollars (Tsujimura p.104).

Even though such a disparity of income distribution is inevitable for a

difference of economic scales, this gap is still unreasonable, considering that

it is said 70% of coffee’s good flavor is accounted for by high quality of

beans.

Finally, it is concerned that a current food system

of coffee might eliminate some farmers’ incentives to produce a variety of

beans with good quality; instead, the world’s coffee market might be filled

with a single profitable breed in the future, and then other flavors would get

beyond an affordable price for the general public. This expectation sounds even

realistic in comparing annual productivity and required minimum price standards

of for maintaining business between Brazilian and Tanzanian farmers. An average

productivity among whole farmers in Tanzania is 172 kilograms per hectare in a

cropping season while that in Brazil almost reaches at 4000; a required minimum

NYBOT price for Tanzanian farmers is 150 US cents per pound though Brazilian

farmers need only 50 (Tsujimura p.91). These huge gaps are explained by a

distinction of their target demand. Beans produced in Tanzania are luxury goods

with their original flavors, while ones in Brazil are for daily-use with

reasonable quality and prices.

In conclusion, relations between concentration of

agribusiness in developing countries and coffee’s food system are analyzed from

three points of view: origins, present issues, and prospects for the future.

Firstly, current intensive business structure of coffee production in

developing nations is turned out to be due to their suitable climate for coffee

production, a remaining tradition of the European colonial age, and a shift to

commercial farming style triggered by international financial institutions.

Then, a case study in Tanzanian coffee’s food system shows an existence of

unfair contracts in coffee trading business, where a variety of beans are not

appreciated well in their price setting. Consequently, such an unreasonable

food system possibly causes a poor diversity in flavors of coffee. This is also

your own problem if you are a coffee-lover.

References

Araghi, F.. 2000. Hungry For Profit -The Agribusiness

Threat to Farmers, Food, and the Environment-. By Fred Magdoff et al.. Monthly

Review Press. P.173-193.

International Coffee Organization. Retrieved July

1st, 2012. http://www.ico.org/

McMichael, P. D.. Hungry For Profit -The Agribusiness

Threat to Farmers, Food, and the Environment-. By Fred Magdoff et al.. Monthly

Review Press. P.147-172.

Toyoda, T.. 2001. International Development in the

Age of Agribusiness -Trade of Agro-Food Products and Multinational

Corporations-. Nobunkyo.

Tsujimura, H.. 2009. Economics of Coffee-Bitter

Reality of Kilimanjaro-. Ota Press.